Whew, a lot of pressure on the first “real” blog post. And there are so many things I could talk about!

- For now, John Warner’s take is about where I’m at regarding ChatGPT. I don’t teach a course that’s likely to be very affected by AI until next spring — at which point, no doubt, the technology will be very different from today. Maybe I’ll have to work out my thoughts more carefully before then.

- I don’t know if this is such big news everywhere, or just here in Minnesota; anyway, no one needs my hot take on what happened at Hamline. I’ll defer to nuanced takes from Muslim organizations and commenters (unpaywalled link).

- This article in The Verge is a good review of the whole Twitter fiasco of the last few months.

I had a strong reaction as I read “The Terrible Tedium of ‘Learning Outcomes’” (unpaywalled link). All I could muster at the time was a cliché . Maybe here I can develop my reaction more.

This article is the first time I’ve encountered Gayle Greene. She is apparently an accomplished scholar and professor emerita. It’s important to point out that her essay in the Chronicle is adapted from her current book, Immeasurable Outcomes, which I haven’t read. I’m sure the book has room for much more nuance and qualification than the essay. It looks like the book is a strong defense of liberal education ideals — I bet there is a lot in there I would agree with.

I find it striking that there is positive blurb there from Lynn Pasquerella of the AAC&U. They articulated the essential learning outcomes of a liberal education and promote a method of assessing student learning of those outcomes. Yet Greene’s essay is a protest against ideas like those.

Maybe her essay is a deliberate provocation. Consider me provoked (cautiously).

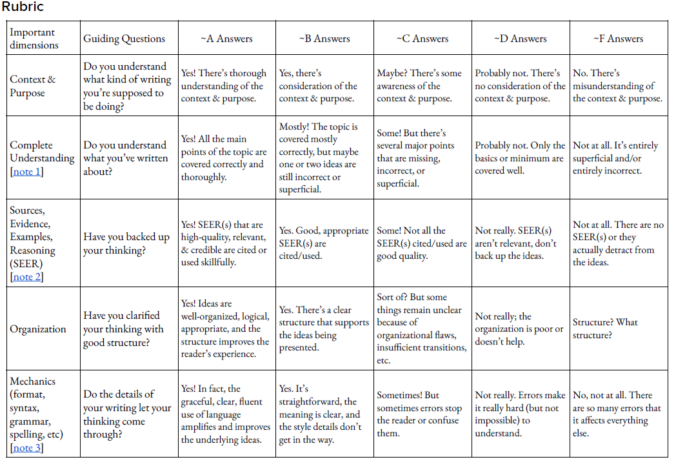

The air is abuzz with words like models and measures, performance metrics, rubrics, assessment standards, accountability, algorithms, benchmarks, and best practices. Hyphenated words have a special pizzazz — value-added, capacity-building, performance-based, high-performance — especially when one of the words is data: data-driven, data-based, benchmarked-data. The air is thick with this polysyllabic pestilence, a high-wire hum like a plague of locusts. Lots of shiny new boilerplate is mandated for syllabi, spelling out the specifics of style and content, and the penalties for infringements, down to the last detail.

Gayle Greene, “The Terrible Tedium of ‘Learning outcomes'”

I get it. There are some of these corporate-ish words that set my teeth on edge, too. “Scale” is one of my pet peeves. It always feels like a way to dismiss anything that’s good as not good enough; “Yes, that’s great, but how does it scale?”

Greene’s thesis is that the learning that takes place is college is ineffable, unmeasurable, “matters of the spirit, not the spreadsheet.” Her characterization of the current machinery of learning outcomes and their assessment as “pernicious nonsense” captures a feeling that I know many in higher education share. When these processes are approached from a perspective of box-checking, of compliance, then I agree, it is not a good use of anyone’s precious time. But what if the ways that these processes work are the bathwater, and the purpose these processes ought to serve is the baby?

In passing, Greene links to this comment: “… while we are agonizing about whether we need to change how we present the unit on cyclohexane because 45 percent of the students did not meet the learning outcome, budgets are being cut, students are working full-time jobs, and debt loads are growing.” I’d suggest that these are real problems and that learning outcomes assessment has nothing to do with them. In fact, learning outcomes assessment is how you know that 45% of your (I presume organic chemistry) class doesn’t understand cyclohexane — and isn’t that useful information?

When she mentions these real problems in passing, I suspect assessment is just the punching bag taking the brunt of the criticism for the fact that higher education today is not like the halcyon days of yore. But let’s disrupt those nostalgic sepia-toned images of the past to also remember that higher education then served a much wealthier and far less diverse student body. Higher education today must learn to serve much greater diversity, families that are not so well-connected, and students who come with a greater variety of goals. Data — yes, some from assessment processes — are tools for helping us do a better job working toward those worthwhile goals.

I’m not being snarky here: I wonder what Greene would do with a student’s essay if they claimed they “understand Shakespeare’s use of light and dark in Macbeth.” Wouldn’t she ask the student to elaborate further, to demonstrate their understanding with examples, with (dare I say it) evidence? Why, then, is it any different when we look at our own claims? If we claim that students are learning things in college, then shouldn’t we be able to elaborate further, to demonstrate how we know they learn those things?

I think maybe a major stumbling block is the issue of objectivity. She writes, “But that is the point, phasing out the erring human being and replacing the professor with a system that’s ‘objective.’ It’s lunacy to think you can do this with teaching, or that anyone would want to.” I teach physics, so my humanities colleagues might expect me to be a major proponent of “objective” and quantifiable measures. But surprise! I think this is a misunderstanding of the assessment process.

Surely mentors read and commented on the chapters of Greene’s dissertation. That feedback was assessment but no one claimed it had to be objective. In fact, one of the most common complaints of graduate students is that different mentors on their dissertation committees give contradictory feedback. That’s just the way it goes.

I wonder if thinking of the dissertation helps in another way: Some faculty just seem convinced that critical thinking skills are, by their very nature, not assessable. But what were your mentors doing when they commented on your writing? Greene ends by saying, “We in the humanities try to teach students to think, question, analyze, evaluate, weigh alternatives, tolerate ambiguity. Now we are being forced to cram these complex processes into crude, reductive slots, to wedge learning into narrowly prescribed goal outcomes, to say to our students, ‘here is the outcome, here is how you demonstrate you’ve attained it, no thought or imagination allowed.'” Did she feel there was no thought or imagination allowed when her mentors clarified what they wanted to see from her, when she was a student?