“To transform the world, education needs to be transformed.” -UNESCO Futures of Education Report

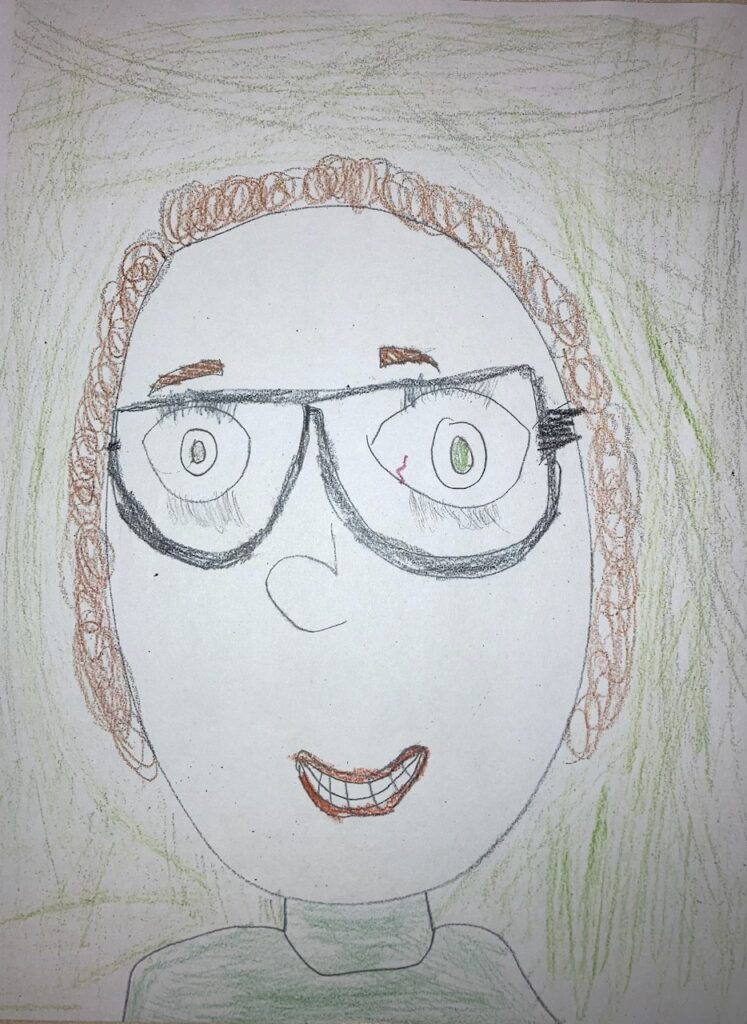

This image perfectly illustrates why I LOVE my job. I truly do–even on days when I’m tired, going to work and being with kids all day is truly a gift. I love my students. I also worry about them–losing sleep sometimes. I strive to provide for my students what I want for my own two kids. I feel the weight of doing my job well, because I have a classroom full of students who are counting on me to give them my best. I don’t take this lightly. Probably because of this, I spend a lot of time in research and a lot of time in conversations with educational colleagues near and far. I know, as a system, we have much work to do.

Recently I stumbled upon a video made to highlight the work UNESCO is doing to globally reimagine and transform education systems. Clearly, I do not run in the same social or professional circles as these global leaders. However, I (and many of my colleagues around the state and country) also recognize the need for major overhaul in educational practices. In fact, I began my doctoral program journey several years ago with no specific end goal in mind, but with a very persistent urge to engage in the work of repairing and replacing a system that is broken, one that fails many of our learners and ultimately our communities and society at large. These thoughts are not meant here as hyperbole, as data upon data have illustrated how our dated systems do not meet the needs of all of today’s learners.

I know and work with a lot of truly wonderful, gifted-at-their-craft educators who pour their hearts, souls and minds (as well as freetime on many evenings and weekends) into the students in their learning spaces. I know and admire many educators who work for equity and who see the immense value of all our learners. I see colleagues who look past behaviors and meet children where they are, with what they need. I know without doubt that in countless classrooms, incredible things happen every day.

And yet, transformation of the full system seems out of reach for the students (globally) who most need it now.

As we hear about how our students are performing academically, as we see a rise in mental health crises, and we hear again and again about gun violence in schools, and on and on with issue after issue, we must reflect on how much has changed in our world since the time many of us as educators, educational leaders, and lawmakers joined the workforce. As the speed of information surpasses our mental ability to keep pace, we must question if our teaching methods attempt to address this. As we see increasing instability in our world (politically, economically, meteorologically, and in social justice), are we addressing that in our spaces? Are we teaching students to question and wrestle with the hard stuff, so they will be able to do that as adults, or do we continue on with our lessons with disregard for the impact these crises have on our communities and families?

I know that schools and districts across our state and country are wrestling with similar issues. With this in mind, I wonder: what is the lever that makes the difference for education as a whole? What is the breaking point at which we will be forced to make significant and drastic changes instead of band-aiding a geriatric system? UNESCO suggests four guiding questions for groups to gather around in these discussions: 1) what should continue; 2) what should be abandoned; 3) what should be reinvented; and 4) what will you do next?

I think to some extent, many of us are waiting for someone else to “fix” the system. While some system shifts have certainly occurred, glacially paced is probably the best descriptor for change within education as a whole. It’s imperative, I think, that more of us feel the persistent urge to get involved–at the very least to push the system, or hopefully, to thoughtfully consider and do the work toward making necessary change. We must find the lever(s), and pull. As I write, I contemplate my answer for question #4: what will I do next? I look forward to organizing conversations with colleagues around the state who are interested in systems change, reflecting on the four guiding questions above. Accountability to this change means we stop thinking about it, we agree to quit admiring the problems we face, and we work toward creating a new chapter in our educational system for generations of students to come, and more importantly for the students in our spaces who need this from us now.

It seems natural follow up that I would ask you to comment: how would you answer the four guiding questions?